Or: How partial client outages in a local network can still be caused by WAN routing issues

I recently spent days troubleshooting an outage in a remote office network and since I had never encountered symtpoms like this before, what follows is a wrap-up of my troubleshooting and research steps as well as a technical explanation. I hope you enjoy the story.

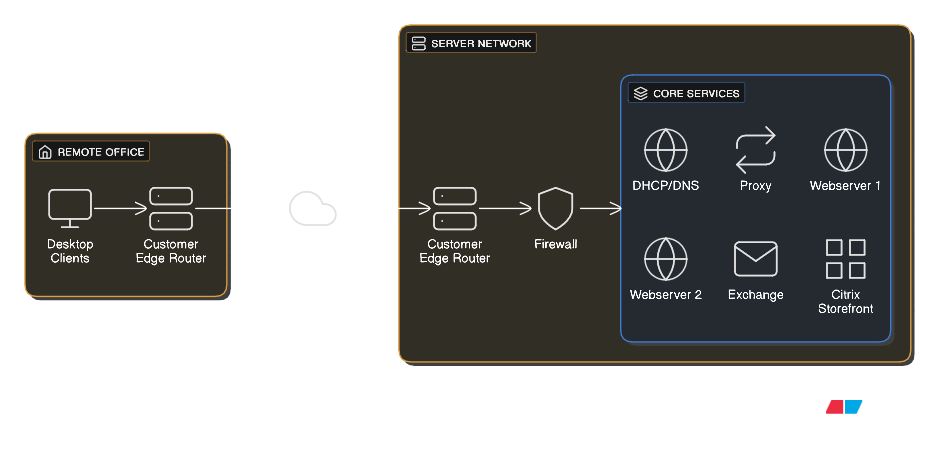

Imagine you are a business or datacenter admin and one morning, in the last week before the calm of Christmas vacation, your worst nightmare comes true – your entire workforce is complaining about service outages. Proxies, websites, apps, virtual desktops, everything seems to be down, but only at first glance. You notice that not a single employee is reporting the same error profile: some may be able to reach the internet via proxy, but cannot login to Exchange, while others cannot even get a Citrix session started. Every client in your network suddenly seems to selectively drop connections to remote services outside the network. Your firewall is overflowing with TCP SYN timeouts, but all of your servers are up and running with processes intact and no errors to be found.

The first thing you notice is that these selective outages seem to be IP-related. Quickly, you connect a test client with static NIC configuration to the network and start building a profile, which is painfully consistent

The client with IP 10.0.0.1 reaches Exchange

The client with IP 10.0.0.2 reaches proxy and webapps

and the list goes on! This renders all coworkers unable to work but causes you the biggest migraine of the year – how can this error profile be so random, yet so.. deterministic?

Of course, you check the firewall for janky policies and all your L3 devices for ACLs that some intern may have cooked up overnight, but you find no changes. Nothing in your infrastructure has changed compared to yesterday.

You begin capturing packets on the servers, ingress and egress firewall ports, as well as on your test client, which is when you notice that all TCP SYN packets arrive at each and every remote server in an orderly fashion, and the SYN,ACK response leaves the correct egress side on the firewall in the same way. But the client never sees those SYN,ACKS…

Right now you have successfully identified that the issue must be arising on the way back to the clients. Something is dropping these packets on the way from the firewall to your client, but the only infrastructure in between those systems

At this point, you have successfully identified that the issue must be arising on the way back to the clients. Something is dropping these packets on the way from the firewall to your client, but the only infrastructure in between those systems is not yours. It’s your provider. So you decide to call them up and present your findings, which prove the packets leave the firewall, but your provider does not trust your findings. You double check and screenshot everything: firewall policies, PCAPs, error messages. Still, the service desk employee remains adamant

“We do not perform any type of IP or TCP based filtering through ACLs or other policies. Your issue must be on the remote office side!”

To finally force the provider to act, you instruct your colleague at the office to disconnect any L2 and L3 devices and simply connect the test client directly to the customer edge router via a client VLAN access port – with the exact same results.

You arrive at an impossible situation: the server firewall is sending TCP SYN,ACK to the customer edge router in a timely fashion, the client directly behind the remote CE never sees them, according to Wireshark. Of course, it does not make sense for the provider to be at fault, they do not filter traffic based on connection profiles, so you understand the response you keep getting from the service desk, but there is literally nothing in the way at this point except for provider infrastructure. With no idea what to do next, your heap of complaints and tickets opened by your users threatening to collapse under their own weight, you aimlessly fire more troubleshooting commands, which is when you notice: From one of the servers, UDP and TCP traceroutes return different results. You had not thought of running a TCP trace for completeness, since obviously routing seemed to be working, and the firewall had always managed to route server responses to the correct interface.

Traceroute Flavors

There are 3 common ways for hosts to execute a traceroute. The core functionality for these is the same, as they all rely on the packets’ TTL (Time To Live) header field. It is 8 bits long, which sets the maximum TTL that can be encoded at 255. The maximum value is rarely used by clients, but network devices make use of it very frequently. At each L3 next-hop, the field is decremented by 1 and forwarded with the new value. Once it reaches 1, the router on which the timer zeroes out will drop the packet and send an ICMP Time Exceeded (Type 11, Code 0) message to the source. This message now contains the router IP as the sender, which is precisely the information traceroute uses. By sending custom packets with increasing TTL starting from 1, the host will receive time exceeded messages from every hop along the way, except if the intermediary was configured not to respond or there is a firewall in the way dropping ICMP.

The first and default implementation for Windows is the ICMP traceroute, in which the host simply crafts ICMP Echo Requests. As discussed, this can be unreliable in a lot of cases.

Secondly, very underrated, the TCP traceroute, where SYN probes are sent using TCP on a specified port, like for example 443. This way, a lot of intermediary systems like proxies and load-balancers are more likely to respond, since the generated traffic simulates generic packets that devices regularly forward.

Lastly, the default for UNIX is the UDP traceroute. In this case, high UDP ports are randomly generated and do not rely on destination ports being open or unfiltered, which makes them application independent

Traffic Flow With ECMP

A common way of load-balancing in WAN environments is per-flow hashing in ECMP (Equal-Cost Multi-Path) Routing. If an autonomous system like a provider network has multiple equally valid options to route a packet, the easiest way would be to load-balance via round-robin method, where packets are sent out via N available next-hops one after another, effectively splitting the load in a near perfect 1/N distribution. This, however, can break TCP connection flow or general packet sequence. Instead, per-flow or per-destination load balancing maps a hash to the number of available next-hops using Modulo N or Rendezvous Hashing and builds that hash using a connection fingerprint. This often is a 5-tuple consisting of source IP, destination IP, source port, destination port and protocol. Reducing the hash result to a number between 1 and N has the effect of routing all flows via the same next-hop, leaving individual connections intact and generally safe from out-of-sequence errors.

This is where you finally realise the cause of your strange network symptoms. This hashing individual connections to fixed paths in the network is a perfect explanation for everything that has been going on today. For different IPs, the same TCP connection maps to another next-hop in the provider WAN in a completely deterministic fashion. With your suspicion based on this knowledge, you ring up your provider again. Finally, you manage to get redirected to a level 2 support tech who is willing to investigate your case. A few hours later you get a call back with a frantic apology: The service center had connected an old MPLS router to the network for maintenance and configuration purposes, but instead of connecting to the management access port as intended, they had wired it up to the access LAN interface, which was still broadcasting the BGP route for the network behind the new device.

Both routes are equally valid from the perspective of intermediaries in the BGP AS, which caused the network to load-balance between the productive router on-site and the old one sitting in the service center. The network statement was promptly wiped and just a couple seconds after this change was committed, all packets now routed back to the office network correctly.

I hope this real case serves as a decent example on how an issue that seems to be application-specific and therefore above L3 in the network might still be caused by routing mechanisms.

Have a great day and never stop learning